![]()

Sunday Travel Section

April 27, 2003

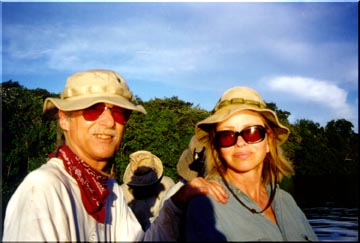

By TIMOTHY LELAND and

JULIE HATFIELD-LELAND

DEEP IN THE PANTANAL, Brazil – At least we agreed on our destination, Brazil.

But we faced a dilemma: One of us (he) wanted to explore the extraordinary wildlife of Brazil's remote Pantanal, while the other (she) wanted to go to Carnival and the beaches and shops of Rio de Janeiro. He had the advantage of the moral high ground -- volunteering on an Earthwatch conservation project -- so, much to her chagrin, he won.

Here's how it went:

He: The animal in the jungle clearing wasn't exactly majestic, I have to admit, but it was the first of its kind I'd ever seen. I held my breath, transfixed, as the runty little creature with the aquiline snout scooted out of the underbrush into the sunlight ahead. Standing beside me in the sweltering heat, beads of perspiration running down her face, my wife was clearly unimpressed. "Is that why we've come here?" she whispered, incredulously. "Did we really travel 5,000 miles to see that stupid little pig?"

Well, yes and no. This wasn't a stupid little pig, mind you, it was a pig-like creature known as a peccary. And not just any old peccary, either -- it was a white-lipped peccary.

She: It was four days before Mardi Gras and I was, as the old song goes, "Flying Down to Rio." Except that I was flying over Rio, bypassing Copacabana Beach and Carnival, to tour the uninhabited interior of the country hundreds of miles south of these world-famous tourist attractions. Did I say uninhabited? Correction. This hot and humid subtropical region is indeed inhabited -- by every living creature that scares me to death. Tarantulas, Africanized killer bees, vampire bats, jaguars, piranhas, poisonous snakes, you name it, all in this wetland 24 times the size of the Florida Everglades.

He: We had traveled from Boston to Brazil to be part of an ongoing environmental study of these and other exotic animals for the purpose of helping preserve one of the richest and most pristine ecosystems in the world. We were volunteers on an Earthwatch expedition seeking to count and catalogue the extraordinary diversity of wildlife in the Pantanal, a vast, seasonally-flooded area south of the Amazon.

Earthwatch Institute, a non-profit organization based in Maynard, Mass., enables lay people with no special expertise (like myself) to join teams of scientists on a wide variety of research projects around the globe, most of them in extremely remote areas like the Pantanal.

She: We flew into the Pantanal in a single-prop airplane, landing on a grassy strip next to our quarters at an old ranch house, leaving civilization behind to stay at the Fazendo Rio Negro. Would I rather be at the fabulous Copa Cabana in Rio? You bet your white-lipped peccary I would.

He: Depending on whether it's the wet season or the dry season, a visitor will either see the Pantanal as a lot of water with relatively little dry land or a lot of dry land with relatively little water. In either case, it is a wondrous sub-tropical area teeming with birds and animals of every description.

She: The temperature is 110 degrees, and the humidity drenches your clothes before you step into them. When I think heat I think bathing suit, but there was no chance of that here, where bare skin is the delight of the smallest predator on the property -- the mosquito. So we pulled on long-sleeved shirts, long pants, and hats, all of which had been soaked in repellant. We also tucked our trousers into long socks and hiking boots, especially when we slogged into the lakes and ponds, where creatures who would love to chew on our feet and legs awaited.

He: Volunteers often work in primitive conditions on these expeditions, but our room at the fazenda was spacious and clean, with a sign over the toilet picturing a frog and explaining: "This small and harmless frog likes humid habitats and may sometimes be seen jumping in your bathroom. It is an important part of the food chain, as it eats mosquitoes. If you would like it removed, please contact the staff."

She: A frog in the bathroom is one thing -- a snake in the bedroom is something else. That's what happened to another member of our group, the resident reptile expert, who discovered that an orange and black coral snake had slipped inside his room during the night.

He: It was non-poisonous, so what's the big deal?

She: The big deal is that I love the outdoors but I don't like snakes and I don't like bats. My first assignment put me into direct contact with the latter, and almost over the edge. As a faithful Earthwatch volunteer I helped set up mist nets in the forest to trap bats, and spent all night in those same dark woods helping pull the repugnant little creatures out of the nets to weigh and measure them. Granted I didn’t actually have to touch them. That job belonged to a handsome young Brazilian graduate student, an Earthwatch researcher named George Camargo -- or "Batman," as I called him. He is regularly inoculated against rabies, and it's a good thing, because he just as regularly got bitten by the vicious little mammals.

Thankfully, Camargo was fun, humming "The Girl From Ipanema," sharing Brazilian brandy, and even showing us some samba steps in between checking the age and gender of the captured bats or putting bat guano into vials of alcohol for safekeeping. (What is it about animal feces that so excites the scientists on these trips?)

He: OK, I admit there are a few "unfriendlies" in the neighborhood. On the day we arrived, a boa constrictor slithered along the edge of a nearby field, and the next morning a black tarantula, its hairy legs spanning the width of a donut, crossed a dirt track in front of us. In the water there are the piranhas and the constant presence of caimans, the alligator-related reptiles that thrive in these wet conditions. But the sights and sounds of this tropical paradise are stunning. Every day you see hippopotamus-like tapirs with long elephantine snouts; dog-sized capybara (the world’s largest rodents); howler monkeys, giant river otters, anteaters, armadillos, crab-eating foxes and jabiru storks, tall enough to look you in the eye.

Sunrise at the fazenda is announced every morning by an ear-splitting cacophony of bird calls. Buff-necked ibis with their long curved bills, dazzling blue parrots, chattering green parakeets, toucans with their outlandishly oversized orange bills, flocks of cuckoos -- all hold forth outside our window with a deafening crescendo of twitters, screeches, toots, caws, and croaks.

She: I like pretty birds as much as the next person, but I also like my sleep. At least the birds weren't terrifying like the bats, or some of the underwater creatures we faced. On one assignment, I helped Donald Eaton from the University of Nevada-Reno net fish and invertebrates in the Rio Negro. Eaton gave me this piece of advice: "Don't pull the net out of the water until it's close to you or the piranhas will panic and chew the net to pieces." I thought he was kidding, but he wasn’t. What am I doing here? Is there anything wrong with the swimming pool of the Copa Cabana Palace?

He: The Copa Cabana Palace will probably always be there; but thanks to humans, the Pantanal might not. Poaching, deforestation, burning, and the discharge of pollutants from mining operations all threaten this extraordinary area. That is why the research of the Earthwatch scientists is so important. The reservation where they work is serving as a laboratory for ways to preserve the Pantanal against human exploitation. Long term, they hope alternative sources of income such as organic ranching, honey farming, and eco-tourism will reduce deleterious impacts on the land. In the meantime, it's a spectacular place to visit.

She: According to Jeffrey Himmelstein, a professor at William Patterson University in Wayne, N.J., who was on our trip, "the greatest travel is in direct proportion to the misery it brings." He may be right. And after all is said and done, I have to admit that watching a flock of roseate spoonbills resting in the shallows of a still pond at sunset is indeed special. So are the brilliant blue (and almost extinct) parrots known as hyacinth macaws that perched outside our window.

But don't believe my husband's loftier reasons for liking the Pantanal. What really turned him on about our ranch, Fazenda Rio Negro, was that there wasn't a place to shop within 200 miles.