Sunday Travel Section

Feb. 21, 1999

VALLEY OF THE MOON, Argentina -- They didn't look like much at first

sight. A few small pieces of purplish rock sticking up in the lunar-like

sand of this desolate desert landscape in northwestern Argentina.

But these weren't rocks. They were the remains of an animal that had died on that spot over 230 million years ago. They were the fossilized bones of a dinosaur.

Two members of our search party had walked right past the site moments before and hadn't noticed them. Now I was sitting on an outcrop of rock in the sweltering heat, drinking water from my canteen, when my gaze fell to the right of my knapsack, lying at my feet.

And there they were -- fragments of mineralized bone glinting in the sand, each with the magenta sheen that is the unmistakable signature of fossils in the Valley of the Moon.

A friend and I had come to this harshly barren but beautiful part of South America to search for the fossils of prehistoric animals as part of an Earthwatch expedition -- a travel experience unlike any other in a lifetime of trips and travels.

Headquartered in Watertown, Mass., Earthwatch is a non-profit organization that sponsors scientific field research throughout the world, enabling people from all walks of life to join its research projects for two or three-week periods as volunteers, writing off the expense as a tax-free charitable contribution. Over the past 28 years, Earthwatch has supported over 2,000 programs in some 120 countries, putting to good and productive work over 50,000 volunteers.

You don't have to be scientifically minded to be an Earthwatch volunteer. The only requirements are a healthy curiosity about our planet and a desire for new adventure. If you fit that profile, Earthwatch trips are made to order.

The problem is deciding which of the many possible expeditions to take -- whether to help track snow leopards in India . . . excavate ancient temple gardens in Pompeii. . . monitor the effects of water pollution on wildlife in Russia . . . document the erosion of glacial sediment in Iceland . . . study black rhinos in Zimbabwe. . . or search for dinosaur fossils in the desert badlands of Argentina.

My old friend, Jim Dean of South Berwick, Maine, voted for the latter. We would go to the Valley of the Moon and look for fossils.

For some reason, my wife had shown no interest in going on this trip, despite our many past travels together. The two of us have bicycled in Spain, white-water rafted in Costa Rica, snorkeled in Bora Bora and skied in France, but the advance billing on this one left her cold.

It may have been the notion of living for two weeks in a pup tent, sleeping on the ground. "Don't even think about it," she declared, declining my invitation.

So I turned to Dean, a former teacher (whose wife was similarly averse to the idea of going). More than 40 years earlier, as teenagers, he and I had traveled extensively together during school vacations. Now -- both 61, both recently retired -- we teamed up once again and headed south.

Argentina is a big country, offering many different climates and conditions within its borders. I had never associated that nation with deserts, however -- not until we reached the Earthwatch camp, located in the northwest near the Chilean border at the foot of the Andes.

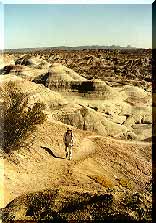

This was Ischigualasto Valley, otherwise known as "The Valley of the Moon," a perfect name for the barren and forbidding terrain. It looked like something out of an Apollo astronaut's photo album.

We had driven the 250 miles there in a four-wheel Earthwatch vehicle from the little town of San Juan, crossing the largest sand dune field on the continent along the way. Known as the Bermajo desert, it seemed empty of all life except scrub brush and occasional hawks that circled high overhead in the thin blue sky. The temperature climbed into the 90's and, strangely, we were alone on the narrow road. There were no other vehicles. No towns. No gas stations. No water. "If the van breaks down on this road it is very bad," said our driver, Nole, in Spanish. "Es una problema."

Five hours later, the macadam turned into a two-track dirt road as we approached our campsite in the valley itself, a five-mile-wide by forty-mile-long depression in the earth's surface, strewn with towering mesas and clumps of ironstone, criss-crossed by deep crevices and ravines, rimmed with high red cliffs and distant blue mountains. This was to be our home and workplace for the next two weeks. As we set up our tent on the bank of a dry riverbed later that afternoon, civilization seemed a very long way away.

Typically, Earthwatch expeditions involve ten or twelve volunteers, of all ages and backgrounds. Our group included a social psychologist from California, a computer engineer from Wisconsin, a college professor from Australia, a teenager on leave from his high school in Colorado and a retired Army colonel from Texas.

None of us had any training in paleontology. One of the most appealing aspects of an Earthwatch expedition, however, is the opportunity it provides participants to learn about new fields of study, taught firsthand by experts. And that first evening, sitting around the open campfire, Dr. William D. Sill, a Harvard-educated paleontologist and leader of our Earthwatch project, gave the group a brilliant shorthand seminar on his research into the origin of dinosaurs.

The Valley of the Moon, he explained, is the only place in the world that reveals a complete sequence of fossil-bearing sedimentation covering virtually all of the Triassic Period -- the 37-million-year span of time between 245 million and 208 million years ago when dinosaurs came to dominate life on earth.

Back then, the valley was an alluvial plain, covered with lush ferns and rich grasses, watered by monsoon rains and rivers that constantly overflowed their banks. The raging waters swept across the land, depositing new layers of sedimentation and, in the process, drowning many of the pre-historic animals that lived there, entombing them in the ooze and mud.

Buried in that fashion, pressed by the weight of succeeding layers of sedimentation, the carcasses of the animals slowly fossilized, as mineral-laden water percolated through their bones, leaving perfect duplicates of the original skeletons.

Today, millions of years later, wind and rain are reversing the process, gradually eroding away the sedimentary rock of Ischigualasto Valley and revealing, once again, the fossilized bones of those very same animals.

Sometimes, the fossils one finds are mere fragments of bone that have been moved from their original resting place. But sometimes they are in their original shape -- "articulated," as the paleontologists put it, still connected in the form of a skeletal carcass. These are the fossil discoveries that make a paleontologist's heart beat faster on first sight. "What kind of animal is this?" they wonder. "Have I found something new?"

There were many different species of animals living on the planet in the early years of the Triassic Period, and most of them weren't true dinosaurs. They were either reptilian cousins of dinosaurs or they were what are referred to as "proto-mammals." (My initial find of fossil fragments, which were too small to identify, may, in fact, have been one of these earlier specimens.)

But something mysterious happened to life on earth near the end of the Triassic period, Dr. Sill explained. Dinosaurs beat out all the other animals in the evolutionary pecking order and emerged as the unchallenged dominant force on the planet. For the next 150 million years or so they reigned supreme.

Many paleontologists are seeking to learn why dinosaurs subsequently became extinct, but Dr. Sill and his team are trying to figure out why they became ascendant in the first place. To that end, they are searching for the remains of the world's first dinosaurs, and they are convinced they will find them in the fossil-bearing sedimentation of the Valley of the Moon.

Which is where the eyes and feet of Earthwatch volunteers such as ourselves come in. For two weeks -- carrying compasses to orient ourselves, water to drink in the searing heat, knives to probe sites in the sand -- we hiked through the lunar landscape of this extraordinary region, searching for fossils.

An eerie solitude envelopes the place, and all who enter it. The rugged terrain seemed to swallow us up as we set out every morning to search the desert floor. Within minutes each person is alone in a vast expanse that holds the untouched mysteries of millions of years.

The silence in the Valley of the Moon is almost palpable. There is no sight nor sound of life, heatwaves the only motion. The sun beats down mercilessly as the temperature climbs to well over 100 degrees.

But one scarcely notices the heat. The lure of fossil hunting takes over and becomes an obsession. Around every arroyo, behind every claystone knoll, on top of every rust-colored mesa, one may find an intact fossil protruding from the sand, the skeletal outline of an animal that lived and died there more than 200 million years ago.

One walks with head down, glancing from side to side, looking for the characteristic shapes and colors that are the fossilized fingerprint of a prehistoric animal. Within a few days, Earthwatch volunteers become expert at discerning the differences between routine concretions of rock and the giveaway purple of ancient bones.

Often you come across little shards of these fossils, washed down from the side of cliffs to the floor of the desert below. Some may be recognizable as part of a vertebrae or a rib -- intriguing but not necessarily valuable from a paleontological point of view because they can't be identified.

Exciting enough, but not a ten-strike.

The real paydirt of fossil hunting is when one finds a skull or the articulated remains of a complete animal.

And on the last day of our expedition, Jim and I hit paydirt. We found both.

We had hiked across the entire valley to have a closer look at the distant ironstone cliffs that turned brilliant red every evening opposite our campsite in the setting sun. It was not an area in which we had expected to find fossils, but on the way back, tired and hot, we stumbled on two articulated skeletons, clearly visible in the desert sand.

One of them we recognized as that of a rhynchosaur , herbivorous creatures that were very numerous at that time, referred to by Dr. Sill as "Triassic pigs." But the other looked different. Slowly, carefully, so as not to disturb the site, we got down on our hands and knees and brought our faces close to the ground for a closer inspection. For several seconds we studied the patchwork of bones that lay before us. And then we both recognized the same thing at the same time: four large, sharp teeth pointing directly at us.

"Cripes," Jim exclaimed, "we're looking at the head of a dinosaur!"

In the end, the head was only part of what excited the paleontologists who came out to view our find.

"This is a proterochampsa!" Dr. Sill exclaimed, after studying the fossilized remains for several moments. "We've only found four others." (Proterochampsas, it turns out, were ferocious crocodile-like reptiles that lived at the time of the dinosaurs.)

But there was something else. We hadn't found one animal -- we'd found two.

"One of them was eating the other," Dr. Sill surmised. "There were two prehistoric creatures here, locked in deadly combat when they died. This is a wonderful sighting."

For an Earthwatch volunteer, words of praise from the team leader are the ultimate satisfaction, worth all the effort and occasional discomfort.

Life on this expedition is not for the fainthearted. Conditions can, from time to time, be trying. Temperatures range from 105 degrees by day to 45 at night. Wind storms buffet the campsite, whipping up the sand and coating everything with a fine dust. The tents are small and cramped. There is no electricity in the camp. There is no running water. We washed from plastic dish tubs with water doled sparingly out from trucked-in waterbarrels. There are no toilets. In fact there were no latrines. When nature called, we grabbed a trowel and a roll of toilet paper and headed into the desert to do our thing and hide the evidence.

But for anyone seeking a trip that mixes a unique learning experience with the thrill of exploration in a beautiful and unusual part of the world, this Earthwatch trip is hard to beat.

Before the trip began, the president of Earthwatch sent the volunteers a letter of welcome, the kind of form letter that one normally ignores as promotional hype.

"You are one step away from an experience that may change your life," he wrote portenteously.

And you know what?

He was right.